Home /Blogs

Blogs

Latest

All Categories

- Africa

- AI

- Bankruptcy

- Business

- California

- Connecticut

- Contract Drafting

- Copyright

- Corporate

- Covid-19

- Cryptocurrencies

- Data Privacy

- Defamation

- Discrimination

- Dispute

- Employment

- Entertainment

- Ethics

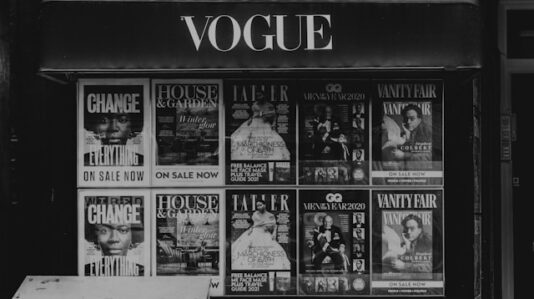

- Fashion

- Florida

- From the blog

- General

- Influencers

- Intellectual Property

- Internet

- Litigation

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Media

- Media Appearances

- Merger and Acquisition

- Music

- Music Publishing

- New Jersey

- New York

- News

- Partnership

- Privacy

- Public Relations

- Retail

- Risk Management

- Sports

- Tax

- Technology

- Texas

- Trademark

- Transportation

- Uncategorized

- Video Content

- Videos

Dec 23, 2025 | Business | Dispute | Litigation Strategies for Resolving Shareholder and Partnership Disputes

Dec 23, 2025 | AI | Dispute | General | Litigation Law School's Trial By AI Jury Highlights Tech's Pros and Cons

Dec 19, 2025 | Business | Litigation | News | Technology FTC Sues Chegg Over “Hard to Cancel” Subscriptions